|

By Jessica Van Mulligen Cost of legal representation and long wait times for a court date are common barriers. A less commonly discussed barrier is the physical layout of the law courts. Physical layout can include signage, seating, the availability of workspaces, or areas that offer privacy. Law is a service profession[1], and the courts are key for legal service delivery. If the way legal services are administered is not meeting the needs of litigants, something needs to change. This need is intensified with the increasing prevalence of self-represented litigants within the legal system.[2] So, how do we ensure litigants using the courts are empowered to the greatest extent? Enter, human-centered design. Human-centered design is a methodology for creating user-focused innovations. Human-centered design “judges a product, service, or system by what the experience of its audience is… [and that] to improve the functionality and experience of a given system, the needs and preferences of the user should be the guide.”[3] Human-centered design targets litigants, not lawyers. Foundational to a human-centered design project is collaboration with skilled professionals. Alberta Access to Justice Week presents an opportunity to collectively strategize how law courts can be reconfigured to be more user-friendly. With decreased traffic in the courts due to COVID-19, now is the ideal time to undertake these collaborative projects.

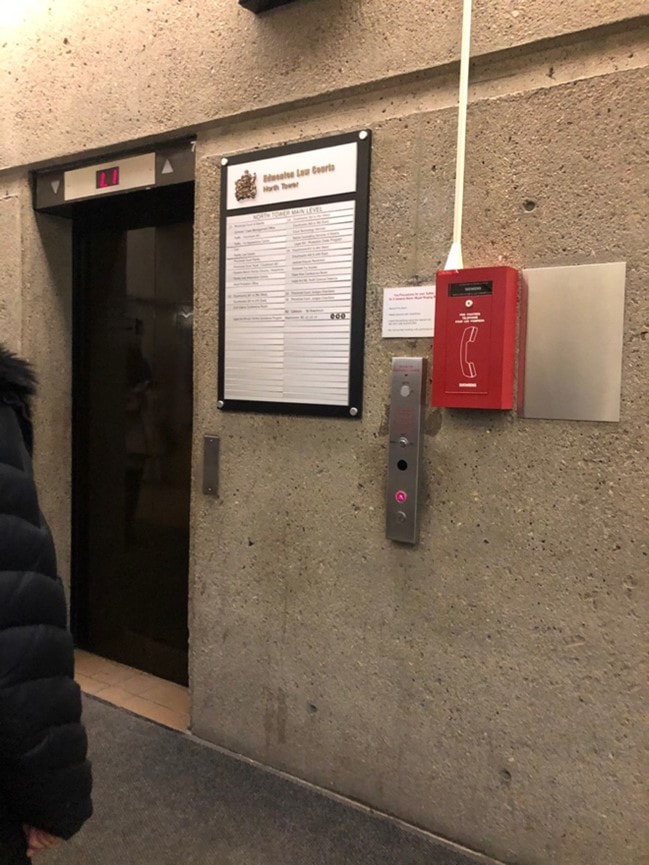

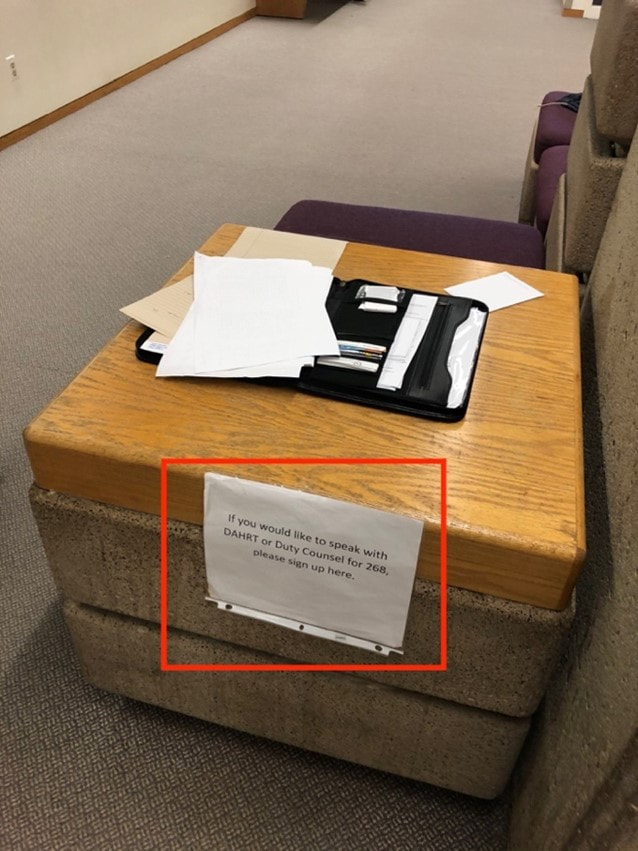

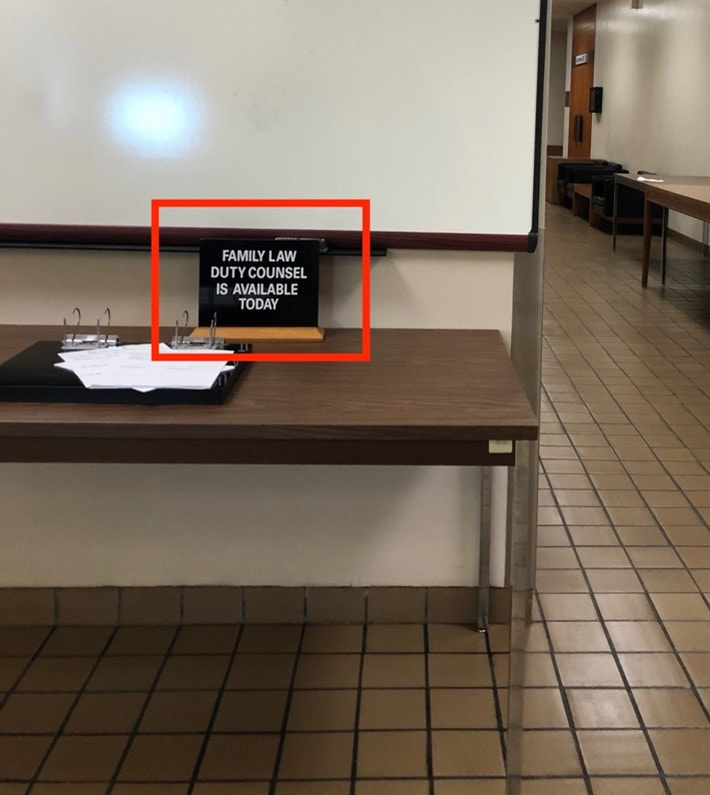

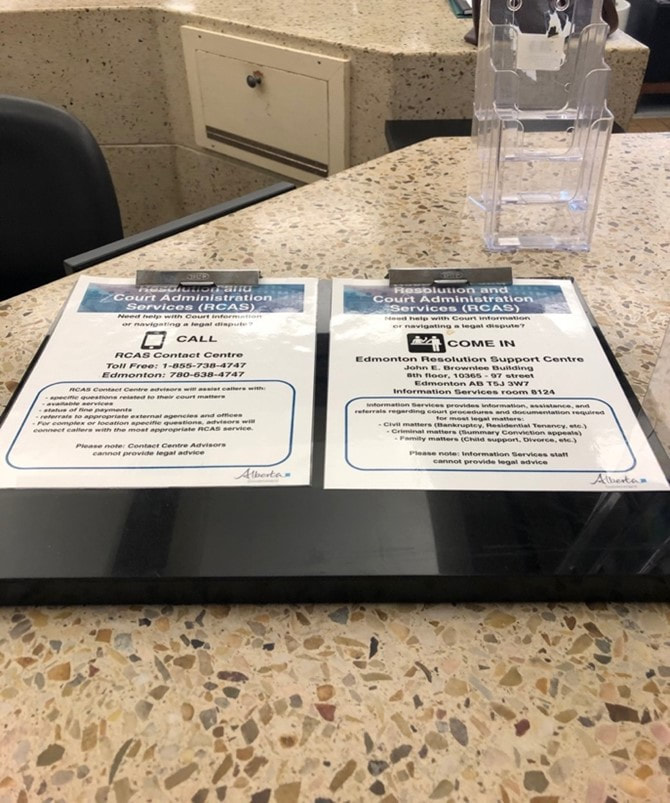

Initiating this collaboration, I offer insight into my observations, informed by human-centered design, from attending the Edmonton Law Courts in 2019. As I navigated the courts, I asked myself two questions: Where are there gaps? What else is possible? I observed several areas to address, but in this post, I highlight the signage at the law courts. After completing a security check, litigants reach an airport-like information board with a list of matters being heard that day (Figure 1). While matters are organized alphabetically and assigned a colour based on the relevant level of court, this colour-coding is not carried over into other official signage. Additionally, the official signage is posted in high-traffic areas like elevator banks (Figure 2), making it difficult to review the information. Signage for legal aid services is particularly confusing because of its inconsistency. For example, Civil Claims Duty Counsel litigants must walk right up to the check-in table to locate the service (Figure 3). Further deficiencies in legal aid service signage include: inconsistent posting locations, limited information provided, obscure sign formats and signage in non-prominent areas (Figures 3, 4, 5). It is troubling that key services to assist litigants are not easily identified at the courts.[4] Human-centered design tackles access to justice issues by ensuring innovations serve litigants who are unfamiliar with navigating their legal journey - innovations accessible to this group will also serve the broader public.[5] With a human-centered approach, litigants can handle their legal issues with greater confidence, knowing that spaces they encounter were designed with, and for, them. Completing this research, I did not consider that a pandemic would so quickly reshape how in-person services are provided. I leave it in your hands, as the reader, to continue reimagining the usability of law courts, perhaps with greater focus on the usability of legal services online. Jessica Van Mulligen graduated from the University of Alberta, Faculty of Law in 2020. She is articling at the Edmonton office of Bishop McKenzie. This post is based on a research paper that she completed for a class in access to justice taught by Professor Anna Lund. ------------------------------------------------------------- [1] Margaret Hagan, “Design Thinking and Law: A Perfect Match”, LawPractice Today (Innovation Issue) (January 2014), online <http://www.courts.ca.gov/documents/BTB24-Precon1G-2.pdf> at 3 [Hagan, “Design Thinking”]. [2] See generally Julie Macfarlane, Final Report, “The National Self-Represented Litigants Project: Identifying and Meeting the Needs of Self-Represented Litigants” (May 2013) (there is an SRL explosion in Canada). [3] Hagan, “Human-Centered Design Approach”, supra note 5 at 202. [4] My quick suggestions to increase usability: colour-coded signs to correspond with the colouring system that already exists on the information screens and digitally map the interior of the Edmonton Law Courts. [5] Shannon Salter, “Online Dispute Resolution and Justice System Integration: British Columbia’s Civil Resolution Tribunal” (2017) 34 Windsor YB Access Just 112 at 124.

4 Comments

7/19/2023 11:45:14 am

Thank you for the sharing good knowledge and information its very helpful and understanding.. as I have been looking for this information since long time.

Reply

7/19/2023 11:47:00 am

Very big and deep thought, forced me to think about what we are doing with us now. We can’t predict future but we can invent it. If we are searching life on mars, then why not we first try to preserve life on earth.

Reply

7/19/2023 11:47:37 am

Thank you for these backlinks because they have been extremely useful in my link building.

Reply

7/19/2023 02:24:25 pm

This collaboration, I offer insight into my observations, informed by human centered design, from attending the Edmonton Law Courts, Thank you for the beautiful post!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |